The Pontifical Council for Culture meets in Rome on 4-7 February 2015 to consider “Women’s Cultures: Equality and Difference.” They’ve issued a preliminary document that tips their hand, in case you entertained any doubts that their ideas about women have changed a whit. It’s titled “Women’s Cultures: Equality and Difference,” and it endeavors — yet again — to convince women of what the male hierarchy insists is their rightful place:

“At the dawn of human history, societies divided roles and functions between men and women rigorously. To the men belonged responsibility, authority, and presence in the public sphere: the law, politics, war, power. To women belonged reproduction, education, and care of the family in the domestic sphere.”

Hold it right there. What happened to female responsibility and authority — women chieftains and medicine women and clan heads? For a long time, it was possible to get away with claiming that public female leaders never existed, but too much documentation has been piled up for this to fly anymore.

“In ancient Europe, in the communities of Africa, in the most ancient civilizations of Asia, women exercised their talents in the family environment and personal relationships, while avoiding the public sphere or being positively excluded. The queens and empresses recalled in history books were notable exceptions to the norm.”

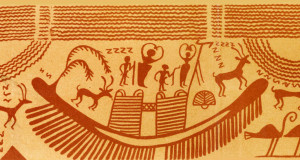

These prelates are advancing a claim of universal male domination — a doctrine to which the church hierarchy is deeply attached. They don’t feel any need to substantiate this claim with evidence. Their fiat has been enough for such a long time, they can’t recognize that the world has moved on. Taking state-based societies as the norm, they pass over long epochs of human history, including neolithic societies with their many depictions of female leadership, and a vast array of Indigenous societies that don’t fit into the cramped sexual politics being touted here.

Women in ancient societies did not “avoid the public sphere”: not the African warriors, nor the Cretan and Iberian priestesses, nor even the Sumerian and Babylonian and Phoenician priestesses. Here we are talking recorded history, that leaves no room for ambiguity. Even in much later periods, we know of Turkic epic singers, the judges and scribes of Cambodia, the powerful market women’s associations of West Africa. But why discuss only these continents, leaving out the Americas, Australia, and the Pacific islands? They also count as ancient societies, and they have their own histories of prominent women, of female law-makers and diplomats and chieftains, of ceremonial leaders and warriors.

The Lady of Cao, a priestess-chieftain in 4th century Perú (a modern reenactment based on archaeological finds)

The Iroquois and Cherokee remember that “mocassin-makers” had the right to act as “war-breakers,” refusing to supply men who wanted to go to war without consent of the women’s council. In Yunnan, the Lisu people say that men had to stop fighting if a woman of either side waved her skirt to call for an armistice. Similarly, on the Pacific island Vanatinai, a woman could give the signal for war or peace by taking off her outer skirt. This is female authority. It is not a fantasy. It is historical reality.

The Pontifical Council’s statement passes over the great majority of Indigenous societies, including those in which female responsibility, authority, and public presence were and remain integral. Among the Six Nations of the Iroquois, the Gantowisas have structural authority to select chiefs and to “knock off their horns” if they fail in their responsibilities. These chiefs act as delegates of the people, not lords over them, a fact that continued to astound European observers who made very different assumptions about leadership, as well as about female power.

But there’s more: the women’s council of Gantowisas (“matrons” in European accounts) discussed issues and, as Seneca historian Barbara Mann writes, the men’s council could not debate any issue until the women’s council forwarded it over to them. They had a structural balance between male and female sovereignty. Mann also calls the women elders the “federal reserve board” of the Six Nations, referring to their control of economic resources.

Hopi women carry out the Lakon ceremony; men have no authority over them in this matrilineal / matrilocal culture.

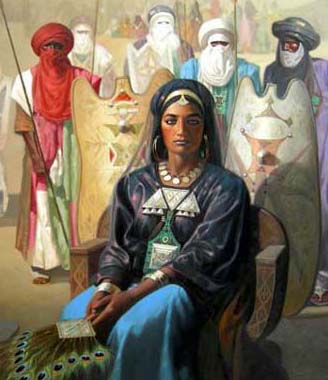

And where, in the priesthood’s blinkered view, where are the female founders, like Ti-n-Hinan, the ancestral mother of the Imushagh / Tuareg people of the Hoggar, whose 4th century tomb is the most prominent monument of the region? What about the female chieftains of the Edomites whose names are listed in Genesis, or for that matter, Miriam the prophetess, Deborah and Huldah? Where are the Montanist prophetesses who were denounced as heretics in 3rd century Asia Minor? The women who led rebellions against conquest and colonization, labor movements, whose actions struck the sparks for the French and Russian revolutions?

The denial of female spiritual leadership is especially fraught for a institution fighting with all its might to hold back the tide of female ordination. To admit the massive evidence for female priesthood — the wu in ancient China, the mikogami in Japan, the mudang in Korea, to name some of the East Asian societies where female shamans once predominated (and still do in Korea) — would be to pull out the last struts supporting the crumbling edifice of an all-male power structure. This hierarchy has been severely shaken by scandals over pandemic child-rapes, and over the cover-ups by bishops, as well as over financial corruption in the Curia. Many people readily declare that women would do a far better job at running the church.

Wu (female shamans) acted as healers, prophets and rainmakers in ancient China. Bronze hu circa 4th century bce

Having pretended that male leadership was a historical universal, an innate and essential quality, the Pontifical Councillors move on to the subect of women’s movements that have challenged and overturned old customary constraints:

“From the latter part of the 19th century onwards, especially in the West, the division of male and female ‘spaces’ was put into question. Women demanded rights, such as that of voting, access to higher education, and to the professions. And so the road was opened for the parity of the sexes.”

That sounds really good, right? That women gained our rights, and things opened up. Oh… wait. Uh-oh: “This step was not, and is not, without problems.”

What were these problems? They tell us: that women were taking on roles “that appeared to be exclusively meant for the male world” [meant, by whom?] and their reflections on their situation were “sometimes becoming entwined with political and strongly ideological movements.” These realizations, we are meant to understand, are far more problematic than the “strongly ideological” doctrines of female subordination that the institutional church has enforced through “political” means, from crusades to inquisitorial trials and witch hunts, to the modern laws and policies the church espouses, that still make women second class citizens whose lives and very bodies are expendable.

The Pontifical Council doesn’t deem patriarchal structures to be problematic; it continues to maintain that they are in line with god-given essential qualities. It is the female pushback against them that it dislikes and deplores. Women! stay in your place.

“Which kerygmatic proclamation [“preaching,” in plain English] should there be for women, one that is not closed in on a moralistic vision? Which indications do we need for a new pastoral praxis, for a vocational path toward marriage and family, toward religious consecration, in view of the new self-awareness that women have?”

What is “new” about pushing women “toward marriage and family”? This much is clear: by “religious consecration” they do not mean female ordination to the priesthood. More likely, they are dreaming up some new religious trappings for the role of wife and mother as a sop to women’s longing for greater inclusion in the church.

The worst thing that could happen, in the minds of the writers, is that women reject the feminine role as they define it: “It is a matter of protecting the dignity of women, respecting what is genuinely feminine (and this is the real equality), and avoiding that the woman, in trying to insert herself responsibly into society that is markedly masculine, lose her feminility [sic].”

This is nothing less than a restatement of the old patriarchal principle: women belong in the private sphere, under the authority of men. Not only that, but “society” means “men.” If women are included in how you think about “society,” there is no need for us to “insert” ourselves into it. We are already part of it. But the statement shows no awareness of that simple fact. These high-ranking prelates don’t believe that women belong in the public sphere at all — and least of all the priesthood.

In fact, they don’t really want women’s input in this initiative on “Women’s Culture.” As Soline Humbert informs me, “The Pontifical Council for Culture has 32 permanent members, all male, appointed for 5 years. Almost all are cardinals, bishops and priests, and a couple of lay men (“men of culture”…No “women of culture”…) There are also Consultors who are appointed by the pope… There are 27 male consultors, and 7 women, ( if I remember correctly), appointed last Summer by Pope Francis.”

In other words: that’s zero females among the 32 permanent members of the Pontifical Council, while in the outer circle of Consultors the ratio of men to women is 4:1, for a total of 59 men and 7 women. This is who is going to issue a definitive statement on “Women’s Culture” — and they expect that to pass for change, in their initiative to engage Catholic women.

This is a familiar pattern of high priestcraft: barring women entirely from the core of power, and admitting a few carefully screened females to an outer circle, where they are greatly outnumbered (and outranked) by men. Soline adds that “there has been a mention of a group of women working on the outline discussion document now released, but I have not seen the names of the members of that group (anonymous women?) nor how they were selected. In addition, while they mentioned there would be an ‘Open Day’ it seems it’s again by invitation only for a select few….”

The image selected for this initiative is highly symbolic: a naked, headless, armless, legless woman in bondage. It is Man Ray’s 1936 photo “Venus Restored.” This is their idea of Women’s Culture?!? It has already outraged countless women. Soline Humbert sums up the background of this piece on the We Are Church Ireland blog:

“Man Ray had a strong interest in Sade and sadism and there is a recurrent sadistic streak in his artwork, as well as in his relationships with women, characterised by domination and aggression. Man Ray photographed women wearing implements of bondage and enacting scenes of torture. He also helped others, like William B Seabrook realise in real life his fantasies of women bondage.

“What is behind this choice of female bondage image by the (all male)Pontifical Council for culture? Is it the choice of the group of women (Who are they?) behind this document? What message does it seek to convey?”

We may well ask.

The same goes for Pope Francis’ recent scoldings of Pilipina women for their high birth rates, after decades of churchmen steadily advocating the rhythm method! As if abstinence is a real option for most married women in this world. He does not have the least clue about the reality that these women live. When it comes to women, nothing has changed.

Neither has the cold attitude toward Indigenous people, whose enslavement, starvation, floggings, and other abuse in the mission system is being affronted by the planned canonization of Junípero Serra. (See 8:50 >> on linked video, where descendants talk about kidnappings, about their ancestors being starved on 700 calories a day, while being forced to labor, and made to kneel on tiles during the entire Mass, kept in line by guards with whips and bayonets.) In these two important social justice issues, women and Indigenous people, the tone-deaf pontiff does not even pretend to want change.

The backlash against women has even reached liberal San Francisco. It took 16 centuries to get the ban on females at the altar overturned, for a couple of decades, in some places, and now some priests are trying to turn it back. “The Rev. Joseph Illo, pastor at Star of the Sea Church since August, said he believes there is an “intrinsic connection” between the priesthood and serving at the altar — and because women can’t be priests, it makes sense to have only altar boys. “Maybe the most important thing is that it prepares boys to consider the priesthood.”

“The Richmond District parish is now the only one in the Archdiocese of San Francisco that will exclude girls from serving at the altar. Such a decision is “a pastor’s call,” said archdiocese spokesman Chris Lyford. “An altar boy program would be a male bonding experience, one that helps them socialize and develop their leadership potential, Illo said. Girls would still be allowed to perform readings during Mass.” Isn’t that special; girls will be allowed to read out loud.

Mexicana curandera smudging the pope: gifts and blessings from sources yet to receive due recognition

This is not going to fly, because too many Catholics have awakened to the realization that they are the church. The women, especially, know that things must change, because they are the ones who are out there doing the real work, holding things together and picking up the pieces, as the number of ordained men drops and the hierarchy scrambles to find men to be in charge. All this has to change. The option for the poor doesn’t mean much without a recognition that women are the poorest of the poor, the ones who carry a tremendous load, on whose shouders the whole edifice rests. You can’t have a progressive agenda without recognizing that their responsibilities give them a spiritual authority of their own. It’s well past time for the prelates to recognize women’s knowing, women’s authority, women’s rights.